Christopher Lasch on the culture of celebrity voyeurism

Writing in 1965, in his celebrated book The New Radicalism in America, Christopher Lasch was, as so often, prophetic, seeing advertising (which he here called “publicity”) as the ersatz or synthetic “instrument of solidarity” in the consumer culture which came to dominate in the second half of the 20th century and beyond. He is in no doubt about the paucity of that culture, seeing that the highest value it is capable of evoking is a kind of voyeurism, epitomized in the prevalence of celebrity gossip.

“Publicity is to a contemporaneous culture what the great public monuments and churches and buildings of state are to more traditional societies, an instrument of solidarity; but because publicity is only the generalized gossip of the in-group, the solidarity it creates is synthetic. Its myths are manufactured. It turns out products, in our own time an Ernest Hemingway, a James Dean, a Marilyn Monroe; and the legendary quality about these people attaches itself not to their memorable deeds but to their personal habits and idiosyncrasies, their liking to go barefoot or their fondness for cats or their love of motorcycles or their various phobias and neuroses. The whole process appeals not to the sense of history but to the voyeurism which is the strongest emotion, it seems, that the contemporaneous culture is able to evoke.”

~Lasch, Christopher. New Radicalism in America. (p) 1966 Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

Algeria 1830: Legacy of an Occupation

Originally published at LewRockwell.com – April 22, 2004

by Richard Wall

|

|

| French “Redlegs’ — Line Infantry, c. 1840 |

Nearly 175 years ago, between June 12 and 15, 1830, a French army of around 37,000 men invaded what was at the time known as the Regency of Algiers, the ancient North African “land of the Berbers” which lies across the Mediterranean sea from southern France. Today it is Algeria, an Arab nation-state of some 32 million inhabitants.

In the late 18th century this land was part of what was called “the Barbary Coast.” For nearly 300 years it had been home to the cruiser ships of the daring and insolent corsairs (labeled “pirates” by their victims) who raided the mainland of southern Europe, exacting tribute and taking numbers of the population off into slavery, as well as attacking vessels of the maritime powers sailing in the Mediterranean, including those of the not long independent United States.

In 1797 the United States had agreed to payment of an exorbitant tribute, amounting to US$10 million over twelve years, in return for a promise that the Algerian corsairs would not molest United States shipping.

|

|

| The Burning of the USS Philadelphia, 1804 |

To no avail: even this, which was effectively an extortionate protection racket, did not stop the pirates. In 1804 the 25-year old Navy lieutenant, Stephen Decatur, made his name in a daring naval raid on the harbor of Tripoli: he successfully carried out orders to scuttle the USS Philadelphia, which, together with 300 American sailors, had been captured while patrolling in the Mediterranean.

By 1815, Congress was ready to authorize naval action against the Barbary States, the then-independent Muslim states of Morocco, Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli. Decatur (now a Commodore) was dispatched with a squadron of ten warships to make conditions secure for United States shipping and to force an end to the payment of tribute. His successful bombardment of Algiers culminated in a treaty between the United States and the Regency, “done on board of the United States Ship Guerriere in the bay of Algiers on the 3rd day of July in the year 1815 and of the independence of the U.S. 40th.” It contained provisions which latter-day crusaders would do well to heed:

|

|

|

Stephen Decatur, 1779-1820

|

“As the Government of the United States of America has in itself no character of enmity against the laws, religion, or tranquility of any nation, and as the said States have never entered into any voluntary war, or act of hostility, except in defense of their just rights on the high seas, it is declared by the Contracting parties that no pretext arising from religious opinions shall ever produce an interruption of Harmony between the two nations; and the Consuls and agents of both nations, shall have liberty to Celebrate the rights of their respective religions in their own houses.”

~The Barbary Treaties, Article 15, July 1815

Decatur sailed away to Tunis, and the fickle dey immediately repudiated the treaty. The European powers, which had almost agreed at the Congress of Vienna (1814—1815) to unite to “end the depredations of the corsairs,” were galvanized into action, determined to end the piracy and the enslavement of Christians in North Africa. In 1816 an Anglo-Dutch fleet under Lord Exmouth delivered a savage 9-hour bombardment of Algiers, re-imposing the conditions of Decatur’s treaty and placing severe restrictions on the Regency’s shipping: these actions delivered a blow to its revenues from which it never truly recovered.

J M Turner: The Battle of Trafalgar

Meanwhile France, which had established valuable trading posts in the Regency following its revolution of 1789—94, had also suffered at the hands of the pirates. After its disastrous defeat by the British at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, the French Navy held little sway in the Mediterranean. The Algiers Regency saw an opportunity in this decline to ratchet up the tributes and rents it charged to France. Then it awarded to England the trading concessions which had previously belonged to France. This provoked Napoleon in 1807 to instruct his military to survey the Algerian coastline, with a view to possible invasion. The surveyor, one Captain Boutin, identified precisely the best landing place where, 23 years later, France’s troops would land in force.

It took less than three weeks for the French armed forces to achieve their formal victory in the summer of 1830. French dominion was formalized on July 5 by a surrender agreement which was forced on the dey (local ruler), Hussein. Five days later Hussein and his family went into exile in Naples, leaving forever his delightful private garden.

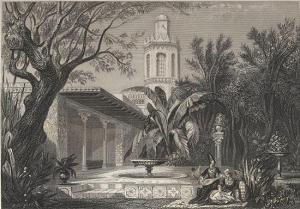

Algiers: The Private Garden of Hussein-Dey

The initial war of occupation, however, was to last some 18 years. Invasion casualties and hesitations saw French military manpower fall to around 17,000 in the difficult year of 1831, but three years later fierce and unorthodox opposition had forced France to increase army numbers to almost double. In 1836 a disastrous and humiliating defeat at the city of Constantine led the French generals to double army numbers again, to over 60,000.

The French Retreat from Constantine, 1836

Achieving victory over the forces led by the man now regarded as the first Algerian national hero, Abd al Kedir, who at one time controlled two-thirds of the country and whose army reached the gates of Algiers, would require an increase in army numbers to 110,000 before it was generally considered, in 1848, that a degree of effective military control had been established. Even then, that control was only over the most northerly part of the country.

The immediate and formal pretext for France’s invasion had been an insult delivered to its diplomatic representative some 3 years before, when the dey had flicked a flywhisk in his face, in an argument over settlement of long-standing financial claims and counterclaims, and the failure of subsequent negotiations to resolve those issues.

The whole enterprise was framed, however, in much more grandiose, civilizational language. In the 1844 version of his book on the history of Algeria (from which the prints included with this article are taken) Léon Galibert, a historian who was generally in favor of “this intelligent and liberal intervention,” reflects on the background to France’s “civilizing mission” in Algeria:

“France took its turn, after so many other famous peoples, to impose its laws on North Africa; to her fell the difficult and dangerous mission of reviving and expanding in this land the civilization which Rome in former times had there deposited. … Islamism, in its deplorable state of decline, was unable to regenerate anything. So a new, strong people was needed, governed by generous notions and the great principle of humanitarianism, to bring Africa out of the mindless state into which it had been plunged by twenty centuries of oppression, war, struggles and invasion….

It must be said in passing, however, that initially the expedition which gave France possession of Algeria was not exactly conceived along these broad social lines, and even less with a view to a permanent establishment. All that France sought was to obtain redress for particular grievances, and only secondarily to smash piracy, abolish the enslavement of Christians, and put an end to the shameful tribute which the maritime powers of Europe were paying to the Regency.”

~Léon Galibert, L’Algérie — Ancienne et Moderne (1st ed.) , Paris, 1844, p. 249

|

|

| Charles X |

The French king Charles the Tenth and his prime minister had actually planned to sub-contract the job out to the ruler of Egypt, Mehemet Ali, who was provided with money, French-crewed warships and all the necessary means of transport for destroying Algiers and putting an end to the piracy.

But the politicians would have none of it: the French monarchy, reeling under the first blows of an emerging liberalism, needed a convenient distraction from its domestic embarrassments. The dazzling effect of a new conquest would cover up and defuse the coming assault on civil liberties. In the mind of Charles the Tenth’s advisors, a French expedition to bring enlightened French values to Algiers and to the dark continent was the key to the success of these long-planned illegal measures, which were calculated, it was said at the time, to give royalty a much-needed shot in the arm.

|

|

| Foreign Legionnaire and Native Infantryman |

There were, as there so often are, deeper forces at work. The king’s plots rebounded on him: hardly had the news of the victory in Algiers reached Paris, when he was overthrown by a new liberal regime which brought in the constitutional monarchy of Louis-Philippe. Members of the new regime were known to be opposed to the Algerian adventure.

Yet the imperial project seemed already to have acquired a momentum of its own, overcoming even their resistance. A parliamentary commission examined the Algerian situation and concluded that although French policy, behavior, and organization there were failures, the occupation had to continue “for the sake of national prestige.”

Even the next revolution, when it came in 1848, did not dampen the national enthusiasm for the colonial undertaking. In that year the three Algerian provinces which France had created became départements (administrative districts) of France, from then on regarded as an integral part of the homeland.

Alexis de Tocqueville, who had never forgotten the effects of the Jacobin terror of 1794 on his own family, had become a parliamentary deputy after the success of his book Democracy in America. In the 1840s he turned his attentions to Algeria and, in his Writings on Empire and Slavery, argued for the robust prosecution of the imperial task. Although aware of the contradictions inherent in his recommendations (he is said to have written, “we have rendered Muslim society much more miserable and much more barbaric than it was before it became acquainted with us”) he persisted in them, because he believed that colonial expansion was the key to preventing democracy from degenerating into popular tyranny. Daniel Lazare writes:

“Tocqueville claimed to support sovereignty, but at the same time feared that untrammeled popular authority could all too easily devolve into tyranny of the majority. In the absence of any countervailing force, what was to prevent a sovereign people from behaving just as repressively toward their enemies as the ancien régime had behaved toward them?”

The answer, thought Tocqueville, lay in vigorous and aggressive imperial expansion (and no doubt a chorus of today’s interventionist bringers of “democracy” to distant Muslim lands would applaud him). This, he believed, would provide an external outlet for the nation’s vigor, which would otherwise be sapped by the minutiae-obsessed, centralizing and tendentially tyrannical Paris bureaucracy. And so, “while initially optimistic concerning the prospects for peaceful coexistence, he was soon calling on troops to burn Arab and Berber harvests, seize unarmed civilians and “ravage the country” to quell resistance.”

Algiers: City Gate of Bab-Azoun

Colonists had started to arrive in the wake of the invasion: over the years their numbers swelled, creating a new population group which had enough time to consider itself indigenous: it was both successful in exploiting its new territory and fiercely loyal to its own control over it. French dominion over Algeria, which was to last for over 130 often turbulent years, thus became a transformational project, cloaked in the overblown rhetoric of “national integrity” from start to finish.

This made the eventual decolonization and extrication, when over 1 million people departed the country after a ferocious war of independence between 1954 and 1962, perhaps the most difficult and painful example of its kind. At the height of the war, French army numbers in Algeria finally reached some 400,000, sufficient at last to quell the resistance, but not to stop the tide of history at the conference table: finally, in a referendum in 1962, the country voted overwhelmingly for independence.

The Library of Congress country study of Algeria states:

“The FLN (National Liberation Front) estimated in 1962 that nearly eight years of revolution had cost 300,000 dead from war-related causes. Algerian sources later put the figure at approximately 1.5 million dead, while French officials estimated it at 350,000. French military authorities listed their losses at nearly 18,000 dead (6,000 from noncombat-related causes) and 65,000 wounded. European civilian casualties exceeded 10,000 (including 3,000 dead) in 42,000 recorded terrorist incidents. According to French figures, security forces killed 141,000 rebel combatants, and more than 12,000 Algerians died in internal FLN purges during the war. An additional 5,000 died in the “café wars” in France between the FLN and rival Algerian groups. French sources also estimated that 70,000 Muslim civilians were killed, or abducted and presumed killed, by the FLN.”

Hindsight is perfect vision, of course, but maybe a lot of bloodshed, dislocation and terror would have been avoided if the French had got out in 1831, when sound liberal and non-interventionist instincts had first told them to do so.

Links and Further Reading

- Arnold E. van Beverhoudt, Jr., Battling the Pirates of the Barbary Coast (extract from personal website)

- Library of the US Congress, Algeria — Country Study, December 1993

- Daniel Lazare, L’Amerique, Mon Amour, The Nation, issue dated April 26, 2004

- Alexis de Tocqueville, Writings on Empire and Slavery, ed. Jennifer Pitts, Johns Hopkins University Press, September 2003

- Irwin M. Wall, France, the United States, and the Algerian War, University of California Press, 2001

Wisdom in the Age of Information

“We live in a world awash with information, but we seem to face a growing scarcity of wisdom. And what’s worse, we confuse the two. We believe that having access to more information produces more knowledge, which results in more wisdom. But, if anything, the opposite is true — more and more information without the proper context and interpretation only muddles our understanding of the world rather than enriching it.”

https://www.brainpickings.org/2014/09/09/wisdom-in-the-age-of-information/

Bath Literature Festival – Election Special: A political discussion that left me speechless

“Maximum political ignorance dressed up as expertise.” The language of vacuity.

Those who know me, know that I rarely let a chance go by to give an opinion on politics and so-called current affairs. When going to organised political discussions with mainstream journalists, I’m even more likely to proffer a provocative question and get into sometimes heated exchanges with the assembled speakers. But tonight’s discussion, one of the last of the week long Bath Literature Festival, on the upcoming election and UK politics in general, hosted by the BBC business editor Kamal Ahmed, left me so stunned by the lack on any meaningful appreciation of the disenfranchised political landscape, that though fuming throughout at many of the panel’s opinions, I could not bring myself to vent my fury, so futile did I think would be the likelihood of meaningful dialogue ensuing.

Those who know me, know that I rarely let a chance go by to give an opinion on politics and so-called current affairs. When going to organised political discussions with mainstream journalists, I’m even more likely to proffer a provocative question and get into sometimes heated exchanges with the assembled speakers. But tonight’s discussion, one of the last of the week long Bath Literature Festival, on the upcoming election and UK politics in general, hosted by the BBC business editor Kamal Ahmed, left me so stunned by the lack on any meaningful appreciation of the disenfranchised political landscape, that though fuming throughout at many of the panel’s opinions, I could not bring myself to vent my fury, so futile did I think would be the likelihood of meaningful dialogue ensuing.

On listening to the guests, the Guardian journalists Gaby Hinsliff and Rafael Behr and the Times political sketch writer Ann…

View original post 1,679 more words

Carl Jung on the past within us

Our souls as well as our bodies are composed of individual elements which were all already present in the ranks of our ancestors. The “newness” in the individual psyche is an endlessly varied recombination of age-old components. Body and soul therefore have an intensely historical character and find no proper place in what is new, in things that have just come into being. That is to say, our ancestral components are only partly at home in such things. We are very far from having finished completely with the Middle Ages, classical antiquity, and primitivity, as our modern psyches pretend. Nevertheless, we have plunged down a cataract of progress which sweeps us on into the future with ever wilder violence the farther it takes us from our roots. Once the past has been breached, it is usually annihilated, and there is no stopping the forward motion. But it is precisely the loss of connection with the past, our uprootedness, which has given rise to the “discontents” of civilization and to such a flurry and haste that we live more in the future and its chimerical promises of a golden age than in the present, with which our whole evolutionary background has not yet caught up. We rush impetuously into novelty, driven by a mounting sense of insufficiency dissatisfaction, and restlessness. We no longer live on what we have, but on promises, no longer in the light of the present day, but in the darkness of the future, which, we expect, will at last bring the proper sunrise. We refuse to recognize that everything better is purchased at the price of something worse; that, for example, the hope of greater freedom is cancelled out by increased enslavement to the state, not to speak of the terrible perils to which the most brilliant discoveries of science expose us. The less we understand of what our fathers and forefathers sought, the less we understand ourselves, and thus we help with all our might to rob the individual of his roots and his guiding instincts, so that he becomes a particle in the mass, ruled only by what Nietzsche called the spirit of gravity.

Reforms by advances, that is, by new methods or gadgets, are of course impressive at first, but in the long run they are dubious and in any case dearly paid for. They by no means increase the contentment or happiness of people on the whole. Mostly, they are deceptive sweetenings of existence, like speedier communications which unpleasantly accelerate the tempo of life and leave us with less time than ever before. Omnis festinatio ex parte diaboli est – all haste is of the devil, as the old masters used to say.

Reforms by retrogressions, on the other hand, are as a rule less expensive and in addition more lasting, for they return to the simpler, tried and tested ways of the past and make the sparsest use of newspapers, radio, television, and all supposedly timesaving innovations.

In this book I have devoted considerable space to my subjective view of the world, which, however, is, not a product of rational thinking. It is rather a vision such as will come to one who undertakes, deliberately, with half-closed eyes and somewhat closed ears, to see and hear the form and voice of being. If our impressions are too distinct, we are held to the hour and minute of the present and have no way of knowing how our ancestral psyches listen to and understand the present in other words, how our unconscious is responding to it. Thus we remain ignorant of whether our ancestral components find an elementary gratification in our lives, or whether they are repelled. Inner peace and contentment depend in large measure upon whether or not the historical family which is inherent in the individual can be harmonized with the ephemeral conditions of the present.

– excerpted from C G Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections (Glasgow: Collins, 1963): 263-264

Britishisms in America

An interesting article today on the BBC website on how some British English expressions are creeping into American English usage. And some have even “snuck in on cat’s feet”.

Translating Securityspeak into English

Kevin Carson at Counterpunch on the obfuscating language of the National Security State:

http://www.counterpunch.org/2012/08/28/on-translating-securityspeak-into-english/

Babel No More and other books

The myth of Babel, Bellos argues, is not only outmoded but actually harmful. It endorses an idealized picture of all languages descending from a pristine single source, “like a cascade trickling down the mountainside of time, branching out into streams and rivers.” “The supposition of an original common form of speech has been taken to mean that inter-comprehensibility is the ideal of the essential nature of language itself,” which “makes translation a compensatory strategy designed only to cope with a state of affairs that falls short of the ideal.”

This vision of Babel “tells the wrong story,” explains Bellos. What the Bible passage actually reveals is that the ancient Sumerians, with whom the story originated, were already all too familiar with linguistic diversity in 3,000 BC. In this more positive model, translation “comes when some human group has the bright idea that the kids on the next block or the people on the other side of the hill might be worth talking to. Translating is a first step toward civilization.”

Brook Wilensky-Lanford on Babel No More and other books, In Lapham’s Quarterly

The Cult of the Hyperpolyglot

BBC News Magazine has an article on those exceptional individuals who speak 11 languages or more

Scooping an incontinent culture

“We live in an era of immense Information Overload. Which leaves us with only one option: to protect ourselves against the overdose and to filter what comes to us. […]

Science of the Time on Filtering Information Overload